MY FAMILY- (Dr) Homa Tadj Bazyar

You can go to my main website www.bazyar.weebly.com

You can go to my main website www.bazyar.weebly.com

History Repeats Itself

Many of the younger generation in our family have been born outside of Iran, or they have married non-Persians from Germany, France, Austria, Scotland, America, Norway, India, Indonesia and the Philippines. Consequently, the family is a mixture of many nationalities speaking miscellaneous languages but, when they have a family reunion, their common language is English.

They know that they are Persian or half-Persian, but do not know who they are from Persian side. This encouraged me to write a few passages about our family background. I had heard that our family goes back to the time of the Shah Abbas the Great (1587-1629), so I traced and found out that our ancestor was called Allahverdi Khan and we are descended from his son, Emamqoli Khan.

Allahverdi Khan was a Christian gholam[1] from Georgia. He migrated to Iran with his Armenian wife. He entered the Court of the Shah Tahmasp I, converted to Islam and chose a Muslim name. He was trained to serve in one of the new gholam regiments in Shah Abbas’s Court. He was among those known as gholaman-e khasseh-ye sharifeh. He was rapidly promoted. He became the governor of a province near Isfahán with the title of Sultán. In 1595-96 he was the commander of the gholam regiments and at the same time governor of Fars. The next year he became the governor of the Kuhgiluyeh.

Allahverdi Khan was distinguished in Shah Abbas’ victories at Herat and subdued several powerful amirs. He defeated the Amir of Hormoz and took the island of Bahrain which was the best area for pearl fishing and so caused Bahrain to be added to the Safavid Empire in 1591. In this way he enhanced the security for the northern side of the Persian Gulf. He got the title of commander-in-chief and sardar-e lashkar in 1597-98 which was followed by Sepahsalar-e Iran which meant that he was the supreme commander of the army.

The Shah then ordered Allahverdi Khan, the governor of Fars, to conquer the port of Gambrun. In 1613, he assigned his son, Emamqoli Khan, who was the governor of Lar, to carry out the Sháh’s order, but this was not achieved in that year. The next year, after Allahverdi Khan’s death, Emamqoli Khan, who was assigned to this task in his father’s place, took Gambrun together with 200 miles of the sea around it and, as a result, he expelled the Portuguese from the southern part of the Persian Golf. He ordered a castle to be built in an European style near the old one, a little further from the sea. He called Gombrun “Bandar Abbas” after the Shah’s name. With the help of Sir Robert Sherley, he reorganized the army and made it more efficient.

Allahverdi Khan died in June 1613. Eskandar Beig, in his obituary notice describes him as ‘one of the most powerful Amirs to hold office under this dynasty’. During his life-time he founded and ordered many public buildings and charitable foundations to be constructed or established, for example, in 1599 the Si-o-seh pol which is an architectural masterpiece. It is also called Allahverdi Khan Bridge, Chahar Bagh Bridge, and Jolfa Bridge, which connects the city of Isfahan to Jolfa, a town with Armenian residents. He laid the foundation of Madrase-ye Khan at Shiraz, but he did not live long enough for it to be finished. He was a humble person, pure in thought and action. “Shah Abbas demonstrated his genuine respect and affection for him by personally supervising his funeral arrangements. He attended the funeral and paid 150 tumans for the expenses. Then, the day after, he went to the Khan’s House to offer his personal condolences to his family (Ibid, II, p.871; tr., p.1098). He sent his remains to Mashhad to be buried there.

It is said that a few weeks before his death, Allahverdi Khan went to Mashhad on pilgrimage and visited the site which he was preparing for his grave and asked the man in charge about it. He answered that the portico and dome were perfectly ready. We are waiting for your Excellency’s arrival! Those who were present reproached the man but Allahverdi Khan took it as a hint that his time was due (Álamárá-ye Abbási, p.615).

After Allahverdi Khan’s son, Emamqoli Khan, who was the governor of Lar, was also appointed governor-general of Fars in 1613 and was granted the title of Sepahsalar-e Iran. Governing the two states, he attained the rank of Amir of the Divan. In 1619-20 he was in charge of the Shah’s plan to link the head-waters of the Záyandeh-rood (in Isfahan) and Karoon (in Ahvaz).

After his father, he was an important help for the Shah in expelling the Portuguese from the Persian Gulf. These two, father and son, drove the Portuguese out of Gombrun. Then it was the turn of Hormoz and Qeshm islands from which the Portuguese were also eliminated.

Emamqoli Khan governed a wide area across the southern part of Iran as if he was the Shah’s vice-regent. He was very powerful and at the same time very faithful to the Shah. The Shah had complete trust in him and behaved respectfully towards him. The Shah used to receive his private guests and friends in Emamqoli Khan’s residence. He even sometimes in private gatherings exchanged his cigarette with Emamqoli Khan’s for fun.

Emamqoli Khan was so rich that his life style was as luxurious as that of the shah himself. One day jokingly the Shah said to him, “I request Emamqoli, that you spend one dirhem less per day, that there may exist some slight difference between the disbursements of a Khan and a King!” Emamqoli Khan had many sincere friends and panegyrists around him. His residence resembled more a court.

He was a Sufi Muslim and like his father was liberal, broad-minded and tolerant. He helped Teresa, Sir Roberts Sherley’s wife to leave Iran when she was threatened because of her religion. At the end of war with the Portuguese, he set free some of the soldiers who had been left behind and let the residents of Hormoz Island leave for India and Oman.

Emamqoli Khan followed his father in funding and ordering some constructions to be built for public utility. The bridge on the Rood-e kor, know as Pol-e Khan, near Marvdasht on the way from Shiraz to Zarqán is one of those. He ordered the unfinished Madrese-ye Khan to be finished. This Madrese is again another architectural masterpiece.

The first indication of one of our great grand father and his son is given in Ásár-e Ajam by Mohammad-Násir Mírzá Forsat Shirazí, who under the title of Madrese-ha (at Shiraz) writes: ‘ This madrese is located at the Esháq Beig area founded by Allahverdi Khan and completed by his son, Emamqoli Khan. This Madrese is the largest and the grandest of all. It is a place for the most learned scholars to hold their classes and discussion sessions there’.

The trusteeship of this school was granted to the male heirs of Emamqoli Khan and many properties were endowed to support it. Mirzá Mohammad known as Áqá Mirzá Bozorg and his father, Áqá Mirzá Sharif, were descendents of Emamqoli Khan. Both father and son were among the most learned personalities in this period.

Emamqoli Khan, after nearly forty years of loyal service from himself and his father to Shah Abbas and his family, became the victim of the Shah’s grandson, Shah Safi. They say that the young Shah, being suspicious of Emamqoli Khan because of his authority, power and wealth, and also by his mother’s intrigues, summoned Emamqoli Khan’s sons to Qazvin for the feast of Ab-pashan and ordered their heads to be cut off and sent to their father who had not taken part in the feast due to age and being ill. The order was obeyed. Emamqoli Khan was at prayer when they presented him with his sons’ heads. He asked to be allowed to finish his prayers then be killed.

As Persian historians suggest the other reason could be the claim that Safiqoli Khan, Emamqoli Khan’s eldest son, made. He believed that he was the Shah’s son, because his mother was one of the Shah’s slave girls and was three months pregnant when she was granted to Emamqoli Khan as a sign of the Shah’s affection and respect. Safiqoli Khan was very keen to posses the throne and his brothers encouraged and supported him.

Another reason which is mentioned is that Davood Khan, Emamqoli Khan’s brother allied with Tahmures Gorgi and killed the leaders of the Qajar tribe and disobeyed the Safavid Government, so that the Shah was also suspicious of Emamqoli Khan, the Conqueror of Bahrain, Hormoz, Qeshm and other areas of the Persian Gulf, and his head was cut off only because of an imaginary suspicion. The man who united the tribes in the southern parts of Iran, and who had thirty thousand soldiers under his command and had driven the Portugese out, had been executed.

Tavernier and Eskandar Beig Monshi wrote that “this father and son” governed the south part of Iran from Lar to Bahrain and Basra (1594-1619). Having total authority, they were kings without a headgear!

Afterwards the Shah issued the order of the execution of all Emamqoli Khan’s children and members of his family in Shiraz, Lar and other places. Some of those who could escape went to Nairiz, Kerman and other towns.

The histories have mentioned the names of three sons of Emamqoli Khan: Safiqoli Khan, Aliqoli Beig and Fathali Beig. The two latter are those who were killed in Qazvin, but it is said that he had many children, both boys and girls. It is from his daughter that our family is descended, and she was Shah Abbas’ cousin from the father’s side. From Safiqoli Khan’s daughter who married Syed Abd-ur-Reza descends the Moula family in Shiraz. The Eqtedari family in Lar is descended from Davood Khan, Emamqolis’s brother.

Five or six generations ago, that is, from the time of ‘Áqá Mirzá Sharif and Áqá Mirzá Bozorg, our family gradually started to follow the new religious movement which was led by Shaykh Áhmad-i-Ahsá’í (founder of the Shaykhi sect) and Hají Siyyid Kázim-i-Rashtí who believed the promised one in all previous religions would be soon manifested.

Siyyid Alí Mohammad Shirazi whom it is believed to be the promised one declared His mission on May 22nd 1844 in Shiraz. He then was named “The Báb”. Áqá Mirzá Sharif, his son and some others of their cousins were interested in his claim and finally converted to the Babí and then to the Bahá’í Faith. Thus, a small group of Emamqoli Khan’s descendants are Bahá’ís now.

Our Bahá’í family, living in a Muslim society and following Bahá’í rules, tried to omit the time-worn customs but not the time-honoured traditions.

At home the men were doing their best to be fair and considered their wives equal to themselves, the wives and daughters were well educated-most were at least literate. Luckily there was no polygamy, not only because our religion does not permit it, but they did not like it. In our old family still the men married the Muslim girls and left them to practice their own beliefs, including Maryam, Mohammad Hossein’s wife, but finally she converted to the Bahá’í Faith.

Through the years the members of the family were mostly scholars who also showed some sort of artistic talent; and some of them were army officers, farmers, tradesmen, teachers, professors in the universities, and the like.

Mirzá Khalil and Mirzá Mohammad Hossein, grandsons of Áqá Mirzá Bozorg’s aunt from the maternal side, established the first modern boy’s school in Shiraz. These were scholars and their names have been mentioned in some books. In a book called ‘Sokhan Saráyán-e Fars’ they are pictured with some famous theologians with whom they were friends, but their names are not given because of being Bahá’ís!

They have been deprived of their rights as citizens. The majority of the Bahá’ís in the family had to leave their home from 1979, when the Islamic Revolution took place in Iran. The revolutionary government arrested some and executed the husband of one of them, dismissed those who were working in the government and private sectors, prevented their children to study in the universities, but they could attend school on condition they renounced their religion. They cancelled their pensions, social and life insurances, froze their savings in the banks, confiscated their properties, prevented their sick members to use the state hospitals and above all they didn’t give them the passport to leave the country for a short or long time, because their names were added to the back list.

Among this group of the family some preferred to remain in Iran and be active in their faith in spite of all the problems, and some could find a way to go to Latin America or Africa as Bahá’í pioneers in the service of their beliefs. Some went to the United States, Australia and Europe to get citizenship.

[1] In the Safavid period to be a gholam of the Shah in contrast to what the word indicates, was an honourable position and could be the path to fame and prosperity. He promoted them to high office in the army or in the civil service. The Shah permitted them to wear the Qizilbash taj or headwear. According to the French traveller, Jean Chardin: “when we use the phrase the Shah’s gholam, it is the same as saying ‘conte’ or ‘marquis’ in French.”

Bibliography

1. Abu’l-Qasim, Afnan. Ahd-i A’la (The Life of The Bab), edited by: Dr. Homa Tadj Bazyar, Oneworld Publications, Oxford, June 200?.

2. Blake, Paul & Collins Andrey. The Complete Guide to Creating Your Own Family Tree. Foul Sham. London. New York. Toronto. Sydney. 2006.

3. Della Valle, Pietro. Pietro Della Valle’s Travels in Persia. Letters: IX. X. XI and XII \ Letter: XIII, XIV and XV.

4. Floor, Willem. Safavid Government Institutions. Mazda Publishers, Inc. – Costa Mesa, California, 2001

5. Forsat Shirazi, Mohammad-Nasir, Mirza. Asar-i Ajam. Bombay, 1353/1934.

Karimi, Bahman. “Madraseye Khan dar Shiraz”, Iran-e Emruz. 3/7-8, 1320 S./1941, PP. 31-32.

6. Fursat Shirazi, Mohammad Nasir. Asar-i Ajam, hamrah ba muqaddameh va Khatirat-i Zindigi-yi muallif ba Farmanha va tasvir muntashir – nashodeh as Fursat.

7. Galford, Ellen. The Essential Guide to Genealogy, the Professional way to unlock your ancestral history. Editorial Consultant Marshal Publishers, Ancestry.com, London.

8. Müller, C.o. (translator) History and Antiquities of the Doric Race. (Translated from German into English).

9. The National Archives. The family History Project. First published in association with the History Channel, 2004.

10. Yarshater, Ehsan. Encyclopedia Iranica, Vol I ABANAHID, Edited by E.Y. Routledge & Kegan paul, London, Boston & Henley, 1985

11. Yarshater, Ehsan. Encyclopedia Iranica, Vol XIII EBN-AYYASH-E’TEZAD-AL-SALTANA. Ed by. E.Y.Mazda Publishers, Costa Mesa, California. 1988

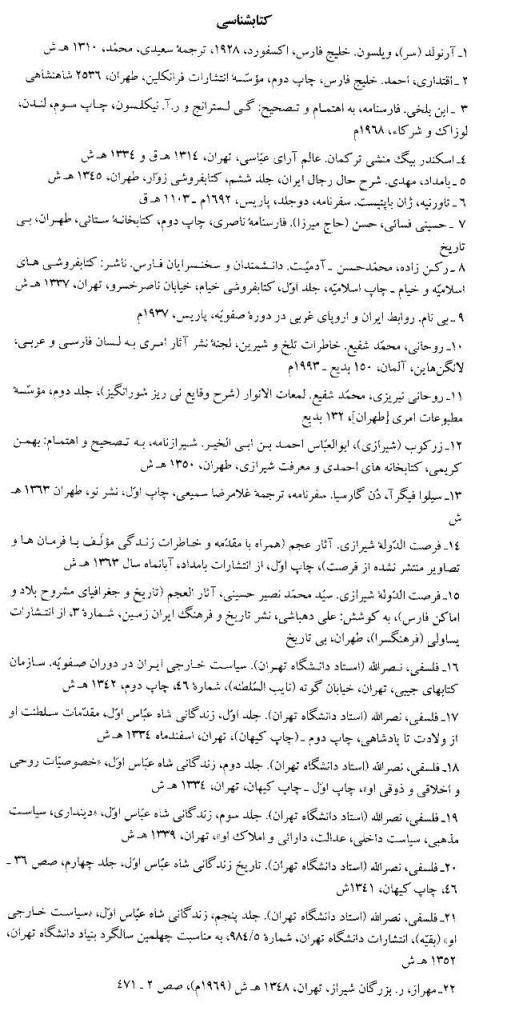

Persian Bibliography

No comments:

Post a Comment